Coming March 20, 2025

☆

Coming March 20, 2025 ☆

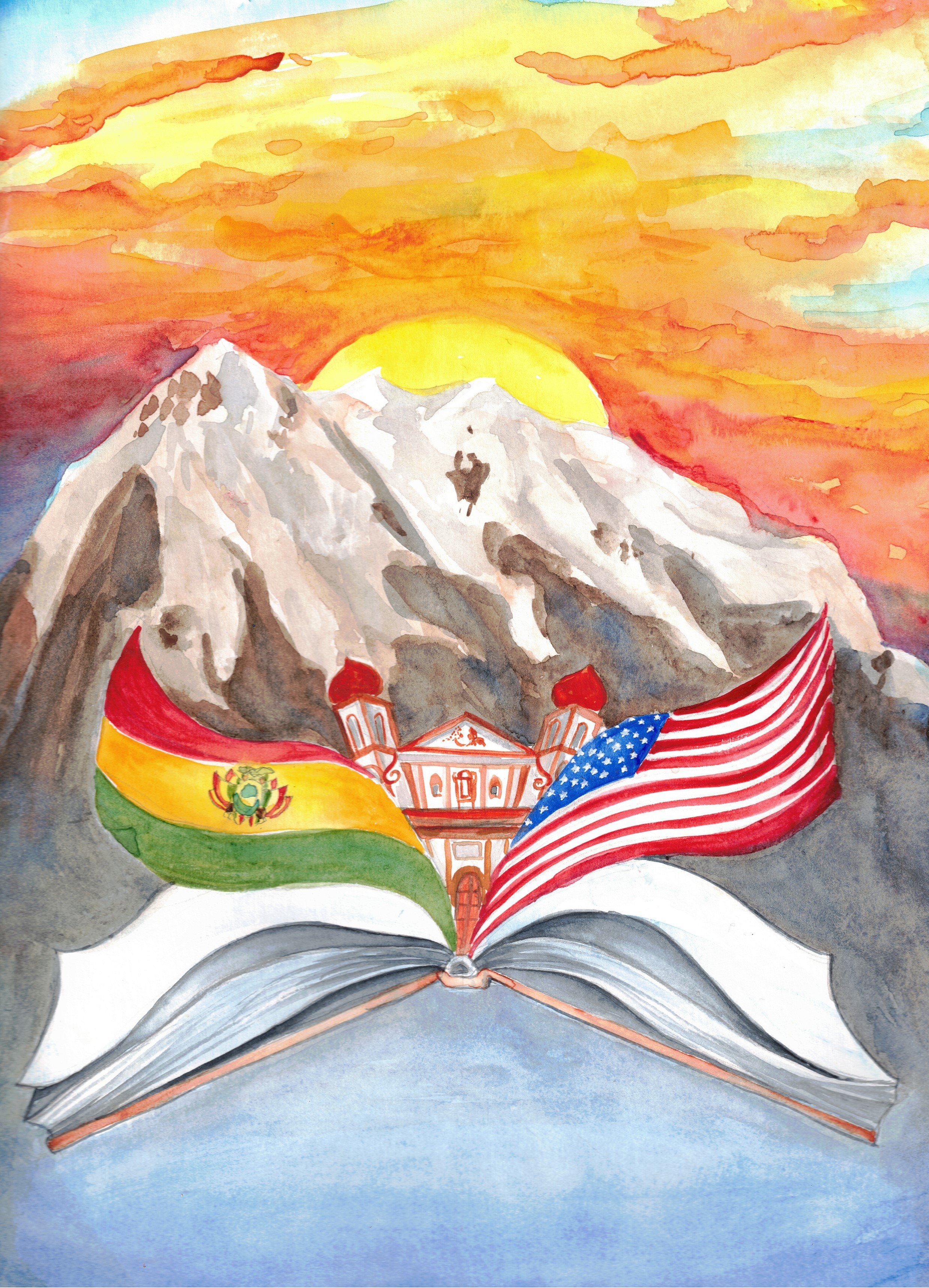

Dreams and Shadows

An Immigrant’s Journey

A memoir by Emma Violand-Sánchez with co-author David Bearinger

Emma Violand-Sánchez knew little English when she arrived in Virginia from Bolivia in the summer of 1961 as a high school senior. In the decades that followed, she would lose a husband in Vietnam, raise two children as a single mother, and become a transformative figure in American public education and in service to immigrants and refugees, advocating for bilingual education and expanding opportunities for immigrant students and their families.

Part testament to the power of suffering and faith and to the challenges women face across the world, Dreams and Shadows: An Immigrant’s Journey is also a meditation on politics, class, the immigrant experience, acculturation as a lifelong process, and the importance of maintaining bicultural identity against the myth of the American “melting pot.” On a deeper level, it is also the story of a life lived in service—and about the ways that suffering and joy are contained each within the other, binding us all together across cultures and boundaries.

Brief Synopsis

Dreams and Shadows: An Immigrant’s Journey is the memoir of Emma Violand-Sanchez, an immigrant from Bolivia who arrived without her parents in 1961 as a senior in high school, knowing little English. During a long and often difficult personal journey, she became a transformative figure in American public education and in service to immigrants and refugees.

Emma has been a forceful advocate for bilingual education. She led the development of a national model for teaching English Language Learners. She began this work at a time when large numbers of immigrants and refugees were arriving in the Washington, D.C. area, first from Indochina, then Central America, and later from scores of other countries worldwide. Many of these new arrivals brought with them the trauma of war and violence, family separation, and deep cultural and personal loss--presenting local educators with an unprecedented challenge.

In response Emma advocated for the approval of the Bilingual GED exam in Virginia and broke new ground as the first Latina to chair a school board in Virginia. She also led the effort to gain in-state college tuition for immigrant students who face challenge due to their immigration status; and founded The Dream Project, which has opened the doors to higher education for hundreds of immigrant and refugee families.

Emma's father was the Bolivian Ambassador to three countries; and partly, this memoir is a story about Bolivia, its political turmoil, the struggles of its indigenous people, and the “glass ceiling” many Bolivian women face. It’s also about the immigrant experience; acculturation as a lifelong process; and about maintaining bicultural identity against the myth of the American “melting pot”.

But mostly, Dreams and Shadows is a story about service and personal resilience. Emma's successes have been extraordinary. So have her struggles, beginning with the death of her first husband in Vietnam. Her personal story unfolds against the backdrops of the Vietnam era, segregation and desegregation, the beginnings of a tidal wave of immigration, convulsive shifts in federal and state education policy, and the emergence of public education as a battleground in America’s culture wars.

Dr. Emma Violand-Sánchez

President Obama & Emma in her role as School Board Chair, Arlington Public Schools

Emma as a baby

Abuelita Julia with Julia, Emma and Susy as children

Emma, daughter Julia and grandchildren Victor and Diego are at the Terrace of the Kennedy Center after attending a children's concert

Emma with first husband Al Giddings at Virginia Tech ring dance

Emma speaking at a Dream Project event

Emma's parents and five sisters reunite in the family home in Cochabamba, Bolivia after 31 years of separation

Emma with her adult children, Julia and James Hainer-Violand

Wedding day with Al Giddings 1967

Emma with two of her grandchildren

Family in Bolivia 1961

Emma enjoying spending time with Jim Weber's granddaughters, Violet Joy and Piper Powell

President Obama's visit to WL High School. Arlington Public Schools Superintendent Patrick Murphy, President Obama, Emma, WL Principal Gregg Robertson

Emma with grandson, Jaimito

Arlington Public Schools - School Board photo with Northern Virginia Community College President Robert Templin, APS Superintendent Patrick Murphy

James Hainer Violand with wife Mariana Rodriguez celebrating Jaimito's birthday

At boarding school in Argentina, Emma was happy to have Ana Maria Parada as a best friend. They were both from Cochabamba, Bolivia.

Six friends, Etta Johnson, Evelyn Fernandez, Maria Isabel Hoyt, Carol Reiger, and Emma were united to share sentiments of loss of loved ones. They formed a Circle of Joy that meets weekly to share experiences and discuss inspirational books.

When Emma was 12 years old, she was sent to a boarding school in Buenos Aires, Argentina for two years. The photos are from San Jose school. It was a catholic school, teachers were nuns.

Arlington County Board member Walter Tejada, Alfonso Lopez, delegate to the General Assembly celebrate Barak Obama's and Emma Violand-Sanchez election to Arlington School Board on November 4, 2008

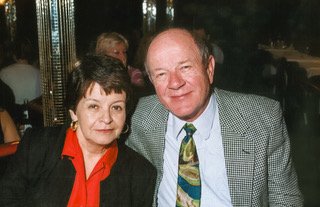

Jim Weber and Emma were partners for 21 years. It was a loving and caring relationship; he died in April 2020.

Emma won first place out of six candidates in the Arlington County Democratic Party School Board endorsement. Walter Tejada, County Board member, supporters and family members celebrate the victory in a highly contested election in 2008.

Emma and her grandchildren Victor and Diego on the Terrace of the Kennedy Center after attending a children's concert

In recognition of Emma's selfless dedication to volunteerism, philanthropy and community in Arlington. The Arlington Community Foundation honors her with the 2018 William T. Newman Jr. Spirit of Community Award. Her 100 year old mother and daughter Julia, were present at the Award celebration.

Latino elected officials, Walter Tejada, Arlington County Board Member, Alfonso Lopez, Delagate, and Emma Violand-Sanchez, School Board member, celebrate Tim Kaine, Virginia Senator and former candidate to the Vice-Presidency, at a Latinos for Kaine event

Emma & Dreamers

Emma and sisters with mother as children

Prologue

I’m an immigrant. Every thread of my identity is wrapped around that core.

I became a citizen of the United States in 1973 and have lived in this country for most of the past sixty years. I’ve immersed myself in the life of my community and my adopted country, but even now, I continue to see myself in that way: as an immigrant, a person whose roots are somewhere else, not here.

Like most of the other immigrants I know, I’ve wrestled--and I still wrestle--with the question of identity: of “Who am I?” It’s a question most people ask themselves at some point in their life journey. But for immigrants, the stakes are higher because our roots are elsewhere.

There’s a saying in Spanish: “No soy de aqui, ni soy de alla,” which means, I’m not from here or from there. Ask anyone who’s come here from another country what that saying means to them, and especially if you ask in the language, they grew up speaking most will tell you: “Yes, it’s the truth.” It’s a truth that almost all immigrants share, no matter where they come from--or how they came.

Every immigrant and refugee I know wants to belong, to shed the label “them” and become one of “us”. The melting pot is part of the American myth, but those who step into it pay a heavy price: laying aside pieces of their identity to become someone they are not, no soy de aqui, ni soy de alla.

I never wanted to make that choice. Instead, my quest has been to embrace my bicultural identity, as a Bolivian American, and encourage others to embrace theirs.

When I was very young, I received a gift. It was a feeling in my heart that I was not separate from those who were suffering. I understood then, in ways I still struggle to explain, that I am “them,” and “they” are me.

And so, I became a weaver, not of cloth but of dreams and shadows. The threads on my loom are family, education, faith, opportunity, service, and the love I have for my two countries, Bolivia, and the United States.

We search for community. I believe that God calls us to work, not in isolation, not by ourselves, or for ourselves, but in service to others. In the Catholic Church, community is, literally, the body of Christ. Which means that we are called to serve community where it exists and to build it where it does not.

The great Vietnamese Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh says that community is an organism, and that we are like living cells within a body whose life depends on each of us in the same way that every cell in a body depends on every other. As Jesus said: “even unto the least of these….”

When I was in my mid-seventies a dear friend wove a tapestry and called it “Emma, weaver.” She attached notes to the threads, naming what she saw as my various accomplishments.

I never knew she’d done this until after she died. But I’ve kept it ever since as a reminder of what my life has been: a weaving of the dreams and shadows of my immigration story, so that others will know and understand that we are not separate.

And that in reality, there is no “them,” only “us.”

— Emma Violand-Sánchez